Don’t Rock the Boat

If you had asked me six months ago what I thought about a minority Liberal government, I’d have been pleased. Just what they needed, I would have said. A check and balance on a corrupt, arrogant party as accustomed to power as a mosquito is accustomed to blood.

Today the result is less pleasing. I didn’t particularly want the Conservatives to win the election either, but I was hoping the Liberals would get a spanking good enough to really hurt them. Perhaps the shock of a minority will be enough to humble Paul Martin, but because the momentum shifted in the Liberals’ favour at the end of the campaign, I fear the optics have been distorted to prevent even that. Instead of offering humiliation, voters everywhere but Alberta and Quebec opted to vote with extreme caution, returning many incumbent Liberals whose seats were thought by many analysts to be in danger.

Many of the so-called tight races, in Ontario in particular, proved to be wide-open after all, proving that the Liberals successfully wooed a majority of the fickle, undecided voters.

Having said all that, the extent to which various media outlets declared the election “decided” early last night is embarrassing. In fact, a key moment occurred very late last night — early this morning here in the East — when the Conservatives finally eked out pea-sized victories in several B.C. ridings.

This argument will have to involve some arithmetic, so apologies to the mathematically-disinclined portion of my readership. In several of those ridings, the closest challengers were NDP candidates, not Liberals. Recounts may yet change the results, but for the moment, the NDP ended up with 19 seats. The Liberals won 135 seats last night, which puts them 20 short of a majority. In effect then, the NDP fell one seat short of truly having the balance of power in Parliament.

Rather than cozying up to NDP leader Jack Layton to make a formal coalition, Prime Minister Paul Martin will now be forced to canvas support from all parties to win votes when legislation is on the table. That may or may not make Martin’s life more challenging — it should at least improve his manners — but it certainly means the NDP cannot hope to have as much influence as they might have had otherwise.

It is disheartening to know that in one riding, the NDP lost by 45 votes. In two others, it was by only a few hundred votes. In any of those places, one wonders how many people were swayed at the last minute and voted Liberal even as their heart supported the NDP. We’ll never know, but it stinks, in my opinion.

Of all the major parties, the NDP were punished the most by our country’s political system, which rewards the winners in each riding at the expense of millions of people whose votes for losing candidates effectively become meaningless.

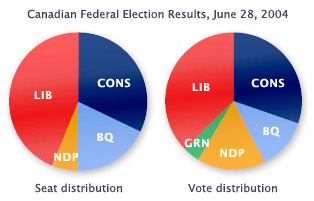

Consider: the Conservatives won 99 seats, or 32% of the 308 available, with 30% of the vote. The Liberals took 44% of the seats with 37% of the vote. The Bloc Québécois — the big winners in a regional system — nabbed nearly 18% of all seats (54) with only 12% of the vote. The NDP won only 6% of the seats, despite getting 16% of the vote. Even worse, the Green Party won no seats at all, despite a respectable 4% of the national vote.

If you look at individual regions, the results are alarming. Overall, in the four Western Canadian provinces, three out of four seats are Conservative, but over half the votes were cast for other parties. In British Columbia, the Conservatives took two-thirds of the seats with one-third of the vote. The NDP had one-quarter of the vote in B.C. but came out with only one-eighth of the seats.

It may sound like just sour grapes from a left-wing voter. To me though, the results of the election last night spell out the need, more than ever, for Canada to adopt a system of proportional representation (PR), where the popular vote a party receives is matched by seats in Parliament. Under a totally PR-based system, the Green Party would have twelve seats instead of none, thanks to their 4% of the vote. The NDP might have 49 seats. And if people knew that their vote would actually mean something, they’d be more likely to vote for the candidate and party they truly support. Both the Greens and New Democrats would likely have done even better, and the NDP would at least gain the position it deserves — to have an influential voice in a government led by common consensus.

I’ve written about this before. There are only a handful of democratic countries on Earth that don’t use at least some form of proportional representation. Regional representation makes some sense in a country as broad and diverse as Canada, but it is clear from voting patterns across the country that, for example, NDP supporters in Toronto and NDP supporters in Vancouver share more in common than NDP and Conservative supporters who both live in Vancouver. Non-Conservative voters in Alberta are not so dissimilar from non-Conservative voters in Manitoba. Why not reward them with a voice in our legislature instead of forcing them to consider the feckless idea of strategic voting, which, as we saw last night, can easily backfire?

The democratic process may well grind down into a crawl during this next government’s term, as members of Parliament re-adjust to building bridges rather than burning them. Fine. Consider it a learning process — that’s the way it ought to be, rather than having omnipotent governments who feel no particular obligation to compromise. True partisans would disagree with me, but partisan politics when unleashed in full is not democracy. We would do well to use the time of any coming political malaise to call upon our representatives for real change in the system.

Previously: Voter, c’est la luxe

Subsequently: From the Department of Homeland Senility

Comments

Thanks for writing this up, and especially for the pie charts. I hadn’t thought about proportional representation much before this election but it is good to see a solid argument for it.

— Kate M. | Jul. 1, 2004 — 11 AM

Couldn’t have said it better myself, Luke. It’s my hope that PR will get an audience in Ottawa before the whole minority government thing implodes.

— mason | Jul. 5, 2004 — 8 PM

Luke:

Good piece on PR.

I could probably be happy with a mixed PR system, as used in Germany and NZ. It maintains the link between member and constituent, which I think is critical, but it also gives some clout to parties that have significant popular support but few (or no) seats.

But my preference is for preferential balloting, as used in Australia. Under preferential balloting, you rank the candidates from first choice to last choice. If nobody takes a majority of first-choice votes, the lowest candidate is thrown out and his or her votes are redistributed on the basis of second choice. The process continues until someone has a majority.

In effect, it’s like the British system of mulitple ballots, but you only have to go the polls once.

Preferential balloting has two major advantages over proportional representation. First, it maintains a strict relationship between member and constituent — no stacking the legislature with members who are only beholden to their party. So it de-emphasizes party influence, where PR emphasizes it. Second, preferential balloting gives significant political capital to small parties, even if they win no seats at all. For example, the Green party can agree to encourage its supporters to put NDP second if the NDP agrees to adopt specific Green policies that aren’t currently on its platform. Or the Greens and the NDP can mutually agree to encourage their supporters to place the other party second, as an informal coalition. That strategy can be especially effective in a vote-splitting situation.

What’s good about the political-capital aspect of preferential balloting is that it moves some of the process of negotiation and compromise out of the legislature (where, let’s face it, it often doesn’t work very well) and into the real world. And it encourages the average voter to think about negotiation and compromise, too. It’s said that in Australia it has lead to a polity more oriented toward compromise and less toward conflict.

As an aside, I think the argument that many other democracies are using PR is a weak one. I don’t believe that the popularity of a particular approach is any use in judging how good it is. I think PR would lead to more divergence in the policies and platforms of the various parties. I doubt that’s a good thing. For one thing, it often leads to the situation where we are forced to choose between policy and integrity, which was clearly a factor in this most recent election. Do you vote for the party with the record of corruption whose policies you like, or another party whose policies you don’t like as much but who you trust more? I think preferential balloting would tend to encourage negotiation and compromise between parties, probably leading to less difference in platforms but, by that very process, freeing voters to weigh integrity more heavily.

— Tedd McHenry | Jul. 6, 2004 — 6 PM

Briefly, I am torn over the question of whether or not proportional representation is a good thing. I agree that Luke’s pie charts indicate a definite flaw in the democracy of our system here in Canada, but I’m not totally convinced that this is a bad thing; what sucks about PR systems is that they give voice to any old crackerjacks who have a desire to influence politics. Sure, maybe one or two seats per extremist nutbar here and there isn’t so bad, but as I understand it, governments in such systems sometimes have to negotiate on occasion with representatives of this kind in order to pass legislation.

— ERK | Jul. 7, 2004 — 1 PM

I disagree with your stance on proportional representation.

I agree that it would lead to a ‘fairer’ system(in theory), and I do agree that our current eletoral system is flawed.

However, it’s clear that in practice, in governments with true PR systems (Israel, Italy), what ultimatly happens is a parliment which is incredibly framented with small fringe parties. Now, this means that many different idealogies get represented - and while in theory this is also good - it means (to take Israel as an example) that Ariel Sharon and his relativly extreme Likud party are able to stay in power over the last decade.

Now, since polls show that most Israelis oppose key stances of the Likud party, it seems clear that this political system works less well than ours in Canada.

As a result, I am firmly against PR.

— Duncan | Aug. 7, 2004 — 3 PM